My Nemesis - Power Idle Approaches

It took me more than two years to obtain my PPL. Between bad weather and fitting lessons around work, I logged many extra hours. It would be easy to blame circumstances, but in truth two major factors held me back.

The first was power-idle approaches.

It wasn’t the startle effect of an instructor pulling the power, nor the emergency procedure itself. It was the fear of needing to go around.

A power-idle approach is essentially the final three minutes after an engine failure in a single-engine aircraft. No matter how well you managed the emergency up to that point, everything depends on whether you actually reach the runway. Missing it by even a few metres means you’re landing somewhere else. That reality stayed with me.

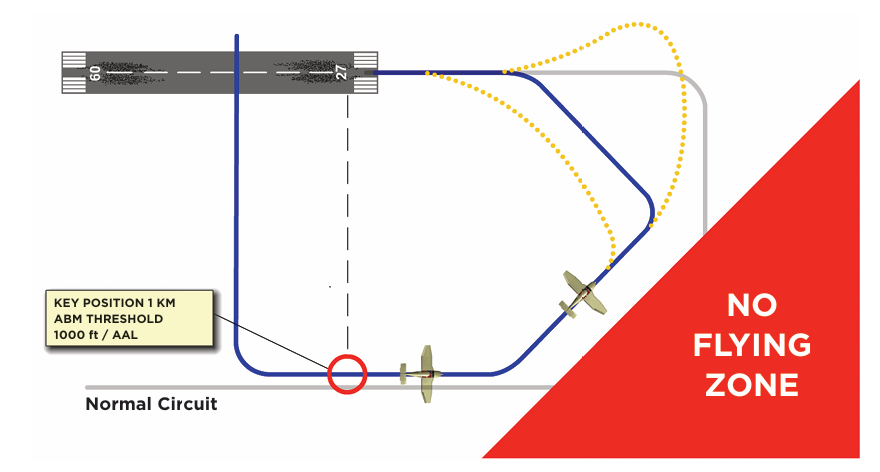

I trained out of Hausen am Albis (LSZN), with 600 m of landing distance and a 100 m displaced threshold. The standard technique was clear: initially aim deep into the runway, then progressively move the aiming point closer as landing becomes assured, finally transitioning to the touchdown zone.

At LSZN this is challenging. The effective touchdown area is already well beyond the threshold, the runway isn’t visible on downwind, and the final is an S-curve through trees. You commit to the glide before you can truly see the landing area.

All of this is manageable. What held me back was the fear of not making it.

So I stayed high and fast.

I carried so much extra speed and altitude “just in case” that I repeatedly failed to reach the runway. I spent many hours repeating the exercise because I did not want to hear, “you would have missed it.” Instructors would reassure me that we would likely have survived the landing, but that wasn’t my standard. I wanted the aircraft on the centreline, within 100 m of the threshold — not somewhere in the overrun.

Eventually the breakthrough came from actually trusting my instructors.

Because the runway isn’t visible on downwind, we established an alternative aiming reference for the blind downwind and base segments. More importantly, I learned to manage energy properly using track and flap — not speed reserve. We flew several power-idle approaches without instruments, forcing me to feel the glide and descent rate rather than chase numbers. That changed everything.

I also learned something deeper about procedures. Published techniques assume standard conditions. Real conditions are rarely standard. Wind shear, turbulence, or obstacles can change the geometry completely. At LSZN, for example, I once encountered roughly 20 kt tailwind above 700 ft AGL that dropped to near calm below. The procedure includes markers where you can extend track if high or fast — but in that situation the terrain and forest limited those options. Judgment mattered more than diagram fidelity.

That realization took time: in an engine-out or any abnormal situation, I am the pilot in command. Procedures provide structure and options, but they cannot guarantee an outcome. Safe outcomes depend on adapting them to the actual situation.

Today I can honestly say I enjoy power-idle approaches.

They are no longer my nemesis — they are one of the most satisfying exercises in flying.